A Spanish-speaking male patient entered the emergency department at Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis, Md., in December 2012 suffering from vomiting, abdominal pain and shortness of breath. Over two days in the hospital, he had blood drawn, underwent an abdominal CT scan, received IV fluids and had a urinary catheter inserted. But it’s possible that he never fully understood that fluid was building up in his abdomen and lungs and that his condition could be fatal.

According to a hospital inspection report, no one discussed his care plan with him in Spanish, the only language he understood, until an hour and a half before he died.

As the U.S. grows increasingly more linguistically and culturally diverse, some safety experts worry that healthcare providers too often are not making professional interpreter and translator services available to patients and families. Instead, they frequently rely on nonprofessionals, including patients’ family members, who are not knowledgeable about medical terminology. This increases the risk of medication errors, wrong procedures, avoidable re-admissions and other adverse events. Nearly 9% of the U.S. population is at risk for an adverse event because of language barriers, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Most organizations advise against the use of a patient’s family or friends, who can potentially do more harm than good. Bilingual clinical staffers also are discouraged from stepping in if they have not been certified as medical interpreters. But physicians and hospital staff often ignore these policies, typically because of time pressures, lack of knowledge about the availability of professional interpreters, or procedural difficulties in arranging for interpreters.

In a report published in May in the Journal for Healthcare Quality, hospital quality and safety leaders, nursing staff and interpreters recounted problems that arose when staffers tried to do without, often because they felt the wait for a professional interpreter would delay needed care. The report found that medication errors and lack of informed consent were more common among patients with language barriers.

Every expert interviewed by Modern Healthcare for this article knew of at least one case where a hospital relied on untrained hospital staff, or a patient’s relative or friend, even at hospitals with established interpreter programs. “Everybody has a story about some risky situation where lack of adequate interpretive services put a patient in harm’s way,” said Melanie Wasserman of Abt Associates, a research and program implementation firm based in Cambridge, Mass., who co-authored the journal article.

In one case, a clinician communicated in French to a Haitian patient who spoke only Creole. Haitian interpreters noted that in French, “estomac” means stomach, but in Creole a similar-sounding word, “lestomak,” can refer to the chest. Such confusion could lead to a procedure on the wrong organ or other body part. “This is a potentially life-threatening error,” Wasserman said.

Many hospitals contract with companies providing interpreters, and most have discouraged the use of children as interpreters for their parents. While most hospitals have established at least phone-based interpretation services, it is not uncommon for hospitals in large urban areas such as San Francisco, Houston or Miami to have more comprehensive interpretation and translation programs.

But researchers remain concerned about inconsistent monitoring and reporting of language-related errors. They say it’s difficult to assess how well providers are addressing the issue, especially since patients with limited English proficiency are less likely than U.S.-born English speakers to call out errors when they occur.

“This is an area where you see some of the worst patient-safety problems,” said Dr. Glenn Flores, director of pediatrics at the UT Southwestern Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, who studies language barriers.

In a 2012 Annals of Emergency Medicine study analyzing audio recordings from visits at two large pediatric emergency departments in Massachusetts, Flores and his colleagues found thousands of what they deemed interpretation mistakes, even among professional interpreters. These included interpreters omitting, adding or substituting words, adding their own perspectives, or using idioms, words or phrases that didn’t exist in the patient’s language. Of these incidents, 18% had potential clinical consequences. Mistakes were less frequent among professional interpreters who had at least 100 hours of training.

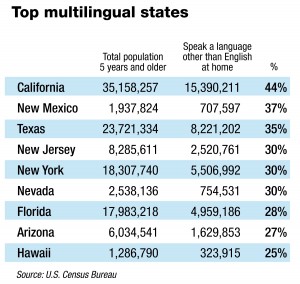

Employment of interpreters and translators is projected to grow 46% by 2022, driven by large increases in the number of non-English-speaking people in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The number of people speaking a language other than English in U.S. homes climbed 158% in the past two decades, a 2013 census report found.

Lucia Contreras of Riverdale, Md., talks with Bertha Castrillon, cultural diversity liaison at Washington Adventist Hospital. The hospital has more than 150 employees who are qualified interpreters and has contract interpreters speaking more than 200 languages.

The Joint Commission requires hospitals to provide professional interpretation services to every patient who needs it. It also requires written materials be tailored to patients’ age, language and ability to understand. HHS’ Office of Minority Health updated its National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services last year, to help hospitals comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Laws on language

In addition, every state has laws on language access in healthcare settings. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia directly reimburse providers for language services used by patients on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. “The fact that states can pay directly for interpreters is a great opportunity to help hospitals meet federal requirements and help them offset the costs,” said Mara Youdelman, managing attorney for the National Health Law Program.

Hospitals in rural areas face particular challenges, said Dr. Elizabeth Jacobs, associate vice chair for health services research at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. The largest rate of increase of people with limited English proficiency is in rural areas because recent immigrants often seek agricultural and other manual labor jobs in rural areas and small towns, she noted.

Some hospitals have staff or contract interpreters for languages commonly spoken in their communities, while others provide interpretation through off-site services by video or phone. Services offered in-person and via video are often preferred, as they allow interpreters to pick up on nonverbal cues that may be culture-specific.

The Office of Management and Budget in 2002 estimated that U.S. hospitals’ annual costs for providing interpreter services was $78 million for inpatient visits, $12 million for outpatient visits and $8.6 million for emergency department visits. An American Medical Association survey found that costs of $150 or more for interpreter services often exceeded a physician’s payment for the visit, presenting what the AMA called a “significant hardship” for practices.

David Fetterolf, president of Stratus Video, which offers professional interpretation services via video, said his company’s professional interpreter service costs about $1.50 a minute. Stratus uses an iPad, often attached to an IV pole, that can be wheeled into a patient room; within 30 seconds a certified interpreter is available online.

Such charges can quickly add up, but many say it is a necessary expense. “We have quite a demand,” said Darrin Bearden, interpretation services coordinator for Northside Hospital in Atlanta. The hospital has an average of 230 interpretation encounters daily, with about 83,000 total interactions in 2013. The hospital started using Stratus in 2012 to supplement other interpreter services it offers, including qualified medical interpreters on staff and telephone services.

Lost in translation

But there is plenty of evidence that continued gaps in interpretation are leading to adverse outcomes. A study published in June in the American Journal of Managed Care found that patients whose primary language was not English were significantly more likely to have multiple 30-day re-admissions at a Los Angeles hospital. Patients speaking Russian, Farsi and Spanish each represented about 5% of patients with three or more hospital stays between July 2009 and December 2010, the study found.

A National Health Law Program study analyzing 35 claims filed in four states between January 2005 and May 2009 for one liability insurer found the insurer paid $2.3 million in damages or settlements and $2.8 million in legal fees for cases where the provider failed to offer a professional interpreter. Among the cases studied, five patients died and others suffered permanent damages, such as leg amputations and organ damage.

Researchers urge hospitals to more closely track the number of limited English proficiency patients and the incidents of errors associated with these patients. Aswita Tan-McGrory, deputy director of the Disparities Solutions Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said hospitals should focus their attention on high-risk situations for interpretation problems, such as medication reconciliation, discharge instructions, informed consent, emergency visits and surgical care.

Some experts say standardization of training and certification for medical interpreters would reduce clinical errors related to interpretation. The National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters, based in Salem, Mass., and the Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters, based in Washington, offer programs testing interpreters’ knowledge and skills, set ethics codes and provide guidelines on standard operating procedures. The certification commission said it has certified more than 1,600 interpreters since it was founded in 2009.

Experts say hospitals also need to do a better job of informing staff that professional interpreter services are available. Even those with established interpretation programs still experience problems.

In the 2012 incident at Anne Arundel Medical Center, which has a professional interpreter program, emergency department nurses had indicated the patient was “Spanish-speaking only.” But there was no record that an interpreter was called during the admissions process. During the patient’s first day, he signed a treatment consent form printed in English, and at one point his daughter acted as interpreter.

It cannot be determined whether the patient or his providers would have done anything differently if a professional Spanish-speaking interpreter had been used throughout his hospital stay. But one thing is clear: The patient “was not able to take part in decisions about his own treatment because his need for a translator was not identified,” the hospital inspection report concluded.

Anne Arundel Medical Center declined to comment on the case, citing federal privacy law. But Victoria Bayless, the hospital’s president, said her facility uses a variety of communication mechanisms to meet the needs of limited English proficiency patients, including personal one-on-one interpretation, video conferencing and telephone services. “We remain focused on continuing to improve our care and service in this regard,” she said in a written statement.

In another reported incident, Washington Adventist Hospital in Takoma Park, Md., acknowledged that its policy was not followed in March when a Haitian patient who spoke Creole was admitted but no professional interpreter was provided during her inpatient stay. Instead, the patient’s daughter provided interpretation.

Marcos Pesquera, executive director for Adventist Healthcare’s Center for Health Equity and Wellness, could not say why the hospital’s staff did not use professional interpreters in that case. But he noted the hospital has more than 150 employees who are qualified interpreters, and also has contract interpreters speaking more than 200 languages, including Creole, via telephone services and video technology. Adventist has since revamped efforts to educate staff about the availability of professional interpretation services. “If the provider has the perception that accessing the resource is hard, they are less likely to use it,” he said.

University of Wisconsin’s Jacobs said long waits and other access issues in getting a professional interpreter are disincentives for busy clinicians and other hospital staffers. “So they go with the easiest thing to do at the moment—their own limited language skills, a family member, or whoever happens to be accessible,” she said. They “don’t readily recognize the impact it can have.”

Originally posted in “Modern Healthcare.”

Rice, S. (2014, August 30). Hospitals often ignore policies on using qualified medical interpreters. Retrieved September 5, 2014, from http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20140830/MAGAZINE/308309945?AllowView=VXQ0UnpwZTVBdmVlL1I3TkErT1lBajNja0U4VUF1VmRFQk1FQVE9PQ==